Making Sense of Consciousness: Projects of the Templeton World Charity Foundation to Investigate Mind-Breaking Theories

Projects to test competing theories of consciousness are raising hopes that we’re making progress on one of science’s most intractable questions. A cloned rhesus monkey is the first one to live to adulthood and a 92-year-old elite athlete teaches us about healthy aging.

It was hard to plan a killer experiment. “Of course, each of them was proposing experiments for which they already knew the expected results,” says Melloni, who led the collaboration and is based at the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics in Frankfurt, Germany. Melloni was the go-between as she fell back on her childhood role.

The collaboration is led by Melloni. is one of five launched by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, a philanthropic organization based in Nassau, the Bahamas. The charity gave US$20 million to five research projects in 2019.

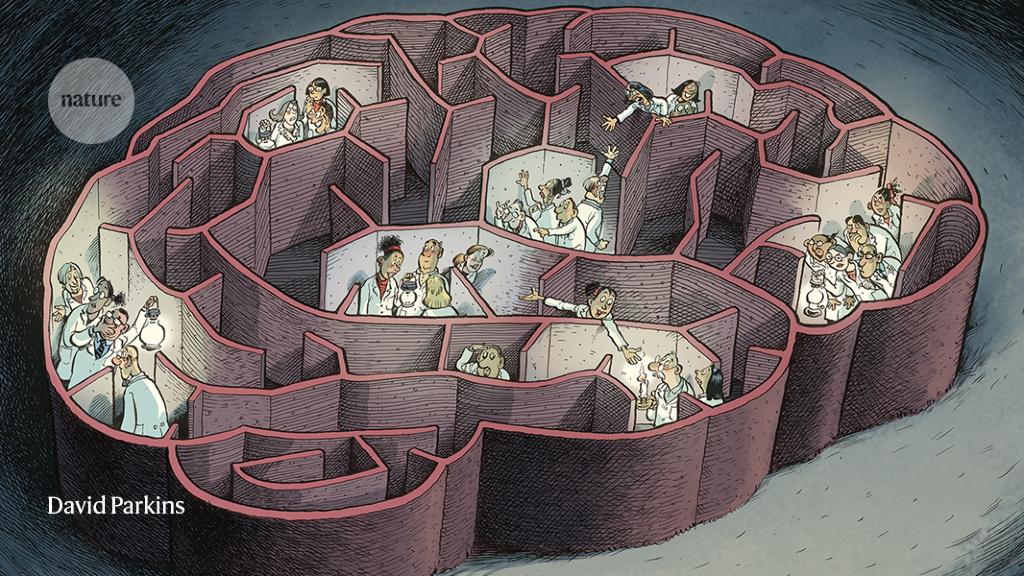

The Brain Wars: can scientists ever agree on how the mind works? A response to an open letter criticizing IIT, Melloni and Kleiner

The open letter was followed by that. Last September, more than 100 researchers signed a letter, posted as a preprint, that critiqued IIT, arguing that its predictions are untestable and labelling it as pseudoscience1. The letter was posted just after Melloni’s collaboration released its results.

Chaos ensued. The letter provoked blowback from other scientists who felt that such an attack could aggravate divides and hurt the field’s credibility. Signatories reported receiving ominous e-mails containing veiled threats. Researchers on both sides of the aisle were affected by accusatory posts. Some even contemplated leaving science altogether.

During his first PhD, in mathematical quantum field theory, Kleiner felt frustrated by the infighting among senior scientists. He says that the field was seen as not making good progress because people were so vocal about other approaches being wrong.

Source: The consciousness wars: can scientists ever agree on how the mind works?

Counting Theories of Consciousness: The Orbit of Jonathan Mason, a Neuroscientist, and the Challenges It Entails

But despite these challenges, many have hope for the future of consciousness science. Leaders of the adversarial collaborations say that their model is already helping to advance the field, even if in small steps. They are just one of many who conduct empirical tests of consciousness theories. Over the past two decades, there have been hundreds of such experiments, a sign of the field’s growing maturity.

Research funders are paying more attention to frontiers in consciousness research, as the US National Institutes of Health demonstrated last June.

And a fresh generation of researchers is leading efforts to cultivate meaningful dialogue and open-mindedness. A Tel Aviv University neuroscientist says that science is a team effort. “It may be naive, but this is my way of optimism: to hope that we are better than that.”

Many theories of how our brains produce subjective experiences and good reasons want to understand the problem more fully are available. It could be helpful in medicine to diagnose awareness in people who are unresponsive; in artificial intelligence to understand how machines will become conscious.

The physical basis of the subjective experience has been explained by multiple theories, which include the hard problem of consciousness and the easy problems such as attention and wakefulness. In an unpublished effort to count them, Jonathan Mason, a mathematician based in Oxford, UK, identified more than 30 theories.

Other front runners include a group of ideas called higher-order theories (HOT), which propose that, for content to be consciously experienced, it must be synthesized into a meta-representation in higher-order brain areas. Another prominent concept is recurrent processing theory (RPT), which suggests that consciousness requires a loop of information flow and feedback. It has been studied mostly in the visual areas of the brain, but should apply to other senses such as hearing or smell.

Theory-neutral authors presented the findings in a preprint, describing how the experiments had challenged both theories in different ways4. The groups defending each theory wrote their own discussion sections, presenting their explanations for the data and how the results meshed with their predictions.

Some scientists who are leading studies believe that Proponents of some theories have made the tests more difficult than they should be. He says that this isn’t applicable to all of the collaborations and depends on how easy the theories are to compare to. But some theorists are described as having big personalities; notably, most of them are men. “I don’t think that’s because women are not doing important research,” says He. “I think that’s mostly because certain people are more willing to come out and talk about big grand theories.”

Neuroscientist Liad Mudrik at Tel Aviv University remembers how excited she was to attend the Seattle meeting that resulted in the collaboration between IIT and GNWT, dubbed Cogitate. She was excited about the process and was writing down everything that people were saying.

She drafted a design based on the discussions that followed her flight back to Israel, and immediately sent it to her colleagues. She says, she was so naive at the time. The ten-month period from that moment on will be the final one.

The team was left with two experiments after they had to decide whether or not to look for various aspects of consciousness. The predictions were made by the team from each theory of what would be seen in participants’ brains. The researchers were able to agree on which theory would be considered a pass or fail for each task.

According to IIT, the task should prompt sustained activation in the back of the brain, which is what the data suggested. However, there was only transient synchronization of activity between brain areas in the posterior cortex, not the sustained synchronization that was hypothesized.

Source: The consciousness wars: can scientists ever agree on how the mind works?

Communication between Tononi and Dehaene: the second experiment and the role of minds in the brains of quantum physicists

The second experiment, for which results haven’t yet been made public, involved participants playing a video game and being asked whether they were aware of certain images shown on the background of the screen.

Having two experiments was a compromise that the team had to make to facilitate consensus between the Tononi and Dehaene camps. “I really admire both of them and I think they are extremely good scientists,” says Melloni. But, she adds, “the world would be a better place if they could give themselves a chance to listen to each other”. Tononi says that the adversarial collaboration allowed him to see the other theories more clearly. Nature requested comments from Dehaene but she did not respond.

Another way to get in touch with the two theorists would be by communicating their ideas from one to the other. “One of the key roles that we have,” says Mudrik, “is to find a common language to make sure that we’re talking about the same thing.”

Source: The consciousness wars: can scientists ever agree on how the mind works?

Tononi’s experience of the Cogitate experiment and the reaction of his colleagues and co-leaders in consciousness research: “We have a problem, we can roll up our sleeves,” says Hirschhorn

Tononi acknowledges how hard the project has been and praises the study leaders — Melloni, Mudrik and Michael Pitts, a psychologist at Reed College in Portland, Oregon — for pulling it off. “They invested so much of their time and passion, rather than doing their own experiments,” he says. “They did a fantastic job.”

When he decided to do a second PhD, this time in consciousness research, he was aware of existing tensions in the field, but felt that people generally got along well. The community felt hopeful about the potential of the adversarial collaborations to produce useful data, he says. The open letter shattered those hopes. Kleiner was determined to do something after being affected by the harsh online interactions. He didn’t want his new field to be perceived the same way as his first. If you can’t heal the division, there is a lot of negative stuff to follow.

When the results of Cogitate’s first experiment came in, Melloni and her co-leaders were not exactly surprised that the two theories’ proponents couldn’t agree on what the data meant.

Hirschhorn thinks that the conflict has been, in a sense, productive. She says people didn’t discuss it explicitly until the collaboration and letter forced it into the open. “I think now we can actually roll up our sleeves and work on this.”

The Promise to the Moon: Protecting the Right Rights of Native Peoples, the Moon for Future Generations, and Improving the Environmental Impact of Global Warming

The lander was supposed to deposit at least 70 people’s ashes on the Moon, but is failing because of a propellant leak. NASA promised to consult with Indigenous Peoples, but that plan was not done. The Moon is seen as an ancient relative by many Indigenous Nations. It’s “not about ownership of the Moon or to enforce Diné religious beliefs,” says Alvin Harvey, Diné of the Navajo Nation and an aerospace engineer. “But rather about the right to be consulted, to uphold Native American legal rights, to hold government agencies accountable and to safeguard the Moon for future generations.”

Glaciers might be able to keep polar ice from melting with the installation of giant underwater curtains near them. The proposal would be difficult to construct, and might interfere with the work of cutting greenhouse-gas emissions. The concept builds on a 2018 proposal in which glaciologist John Moore and three colleagues made a heartfelt plea to consider such bold ideas, given the toll that rising sea levels will take on humanity. We know the pristine beauty of the glaciers and understand the hesitancy to interfere with them. But we have also stood on ice shelves that are now open ocean,” they wrote. “Is allowing a ‘pristine’ glacier to waste away worth forcing one million people from their homes? What is the estimated number of Ten million? One hundred million?”

Source: Daily briefing: Can scientists ever agree on how consciousness works?

Genetically Uniform Monkeys: Cloning the First Rhesus Monkey in the Lab for Drug Studies and Drug-Efficiency Tests

A large amount of gene groups from various ocean organisms have been made accessible online. The database includes more genomic data from the deep sea and sea floor than previous catalogues. More than half of the genes from thet wilight zone came from mushrooms, which is a sign that they play a greater part in organic matter than previously thought. Researchers can use the database to discover new antibiotics or watch the impacts of burning fossil fuels.

A rhesus monkey cloned in the lab has lived for more than two years, its first time living into adulthood. The feat was achieved using a slightly different approach to the conventional cloning technique used to clone Dolly the sheep and other mammals, including long-tailed macaques, the first primates to ever be cloned. The techniques could open up possibilities for the use of cloned primate in research. A lot of genetically uniform monkeys can be used for drug-efficacy tests.