A Time and Space-Time Odyssey: The First Three Parts of Space, Time, and Motion in a Calorimetric Wildland

California is having more and more wildfires because of climate change, poor tree management creating fire hazards, and antiquated power lines. In 2018, the failure of a 100-year-old rusted electrical hook sparked the Camp Fire, the world’s most expensive natural disaster that year. The blaze forced Pacific Gas and Electric into temporary bankruptcy. Journalist Katherine Blunt’s disturbing history of California’s environmental calamity ends in 2021, with the company’s new chief executive announcing costly underground power lines.

Theoretical physicist and philosopher Sean Carroll specializes in quantum mechanics, gravity and cosmology. He aims to create a world in which “most people have informed views and passionate opinions” about modern physics. The first book in a trilogy deals with space, time and motion. Unlike most introductory physics books, the book has mathematical equations, but not solved, as well as the expected metaphorical language.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-03749-7

Twenty Years of Science: Dr. Gregory Morgan’s Crucial Tests of Cancer, and a Philosophical Review of his Life and Work for COVID-19

One-fifth of cancers in people worldwide are caused by tumour viruses such as hepatitis B. Work stemming from these pathogens won seven Nobel prizes between 1966 and 2020, notes historian Gregory Morgan in his authoritative but accessible chronicle. Yet tumour virology is rarely mentioned in discussions of how molecular biology opened our understanding of cancer. Morgan observed that this impedes a full understanding of the field as a technoscientific force.

Humans are so focused on “brain-centric consciousness”, says philosopher of science Paco Calvo, “that we find it difficult to imagine other kinds of internal experience”. Plants may be intelligent. His challenging book is aimed at both believers in this possibility and non-believers. His experiment to induce sleep with a plant that is sensitive to touch, and the fact that Charles Darwin wanted to be buried under an old yew rather than in a abbey, are provoking thought.

Just before anthropologist Dimitris Xygalatas’s university went into COVID-19 lockdown, his students had one main concern: would there be a graduation ceremony? We care deeply about rituals, he notes in his wide-ranging and well-written survey, because they help us to “cope with many of life’s challenges”, even if we do not understand how — the “ritual paradox”. Scientific investigation has been tricky, because rituals do not flourish in a laboratory, but wearable sensors and brain-imaging technology help.

The first-ever vaccines against respiratory syncytial virus are being developed by Pfizer and Glaxo. Nine charts show the failures of UK science to Black researchers and the best books to read this week.

The Big Picture: Why Black people are squeezed out of science, and why artificial intelligence isn’t a big deal in UK academia

Researchers have bolstered the power of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cancer therapies, which use genetically altered T cells to seek out tumours and mark them for destruction. Now scientists have further engineered the cells to contain switches that allow control over when and where the cells are active. It helps them get around immune suppressing defences.

There’s just five Black professors in UK biosciences, one in chemistry and none in physics — figures that have barely shifted in more than a decade. This Nature feature shows, in nine stark charts, how Black people and those from other marginalized ethnicities are squeezed out of science. Black representation at the undergraduate level has been climbing since 2007, but at the postgraduate research level, the number of Black people drops sharply — and only 0.6% of professors are Black. The trend is reversed for white students. There are complex reasons, but biases, lack of role models and not being vouched for all play a part.

Andrew Robinson’s pick of the top five science books to read this week includes a frank and fascinating book from the leader of the UK COVID-19 Vaccine Taskforce, an exploration of how technology can connect us to the sounds of nature and a magnificent revival of mathematician Johann Doppelmayr’s 1742 celestial atlas.

The team discusses the earliest known narrative scene with prehistoric carvings that make up it. They asked if artificial intelligence could end student essays and if there was enough diversity in UK academia.

A climate scientist fromUkraine, a monkeypox watchman, and an abortion fact- finder are some fascinating people behind this year’s big research stories.

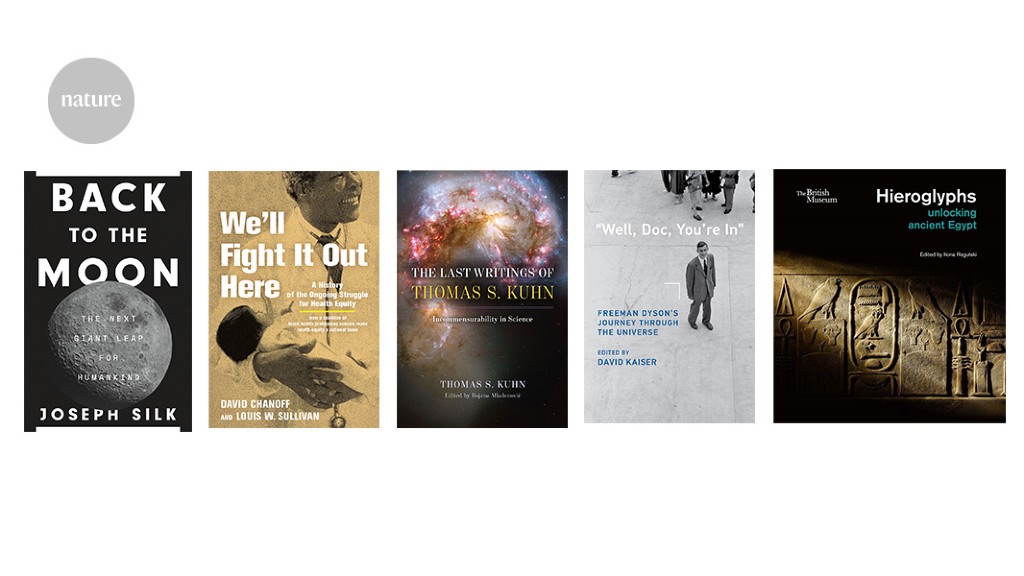

From Young to Regulski: Two Centennials of Ancient Egypt, from Dyson and Kuhn’s Theoretical Physics to the Structure of Scientific Revolutions

The most visited object in the British Museum in London is the Stone that was used to identify Egyptian hieroglyphics, it is a source of fascination. Its decipherment, initiated by polymath Thomas Young and achieved by philologist Jean-François Champollion starting in 1822, “changed our understanding of the ancient world”, says Egyptologist Ilona Regulski, curator of a British Museum exhibition. The two centuries of Egyptology that expert contributors vitalize are outlined in this companion book.

Theoretical physicist Freeman Dyson had a contrarian streak when it came to acceptance into the establishment. After a colleague extolled his work at a 1949 conference, physicist Richard Feynman told Dyson: “Well, Doc, you’re in.” But Dyson proudly never finished his PhD. David Kaiser says that he was a “destructive autodidact who developed a lifelong suspicion of organized curricula”. Hence, perhaps, his early espousal but later denial of the scientific consensus on climate change.

The year after Apollo 11 landed on the moon, Joseph Silk won his doctorate. In this book setting out his vision for the next half-century, he argues with passion for further lunar exploration as soon as possible. He posits that only telescopes on the Moon can realistically probe the origins of the Universe and the possibility of extraterrestrial life. He is aware of the commercial and environmental risks. International legal treaties, he says, must forbid “free‑for-all lunar exploitation reminiscent of the Wild West”.

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) by philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn is “indispensable reading for every well-educated person”, writes philosopher Bojana Mladenović in her introduction to this collection. The texts of two lectures from earlier are presented, with drafts of a reworking of Structure’s philosophy. These inquire if historians can comprehend past scientific paradigm even though they are incommensurable with present science.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-04569-5

Chanoff and Sullivan’s History of Social Inequality: The First Year of COVID-19 and the Foundations of the Association of Minority Health Professions Schools

David Chanoff and Louis Sullivan note that in the first year of the COVID-19 Pandemic, African Americans were more likely to die than whites. Their history of this inequity begins with health during slavery, and focuses on the Association of Minority Health Professions Schools, co-founded by Sullivan in 1976. Sullivan was head of the US Department of Health and Human Services after the group gained national political influence.