Should young children take the new anti-obesity drugs? What the research says: Can the new drugs improve children’s health?

Evidence shows that blockbuster weight-loss medications can reduce obesity even in children aged 6–11 years, but their long-term effects on growing bodies are unknown.

A lot of doctors’ decisions are based on trials in adults. “We need to have evidence from children to inform clinical decision-making.”

The findings in older children are the same as those from the latest trial. A study found that 43% of those who took liraglutide showed a reduction in their body fat, compared to 19% who took a placebo. And in a 2022 trial2, 73% of participants aged 12–17 who took semaglutide lost 5% or more of their body weight, compared with 18% of those taking a placebo.

But 72% of the 82 participants in that study were white, and only 6 individuals were Black, so the results might not generalize to children of colour. More diverse studies are needed, Ball says.

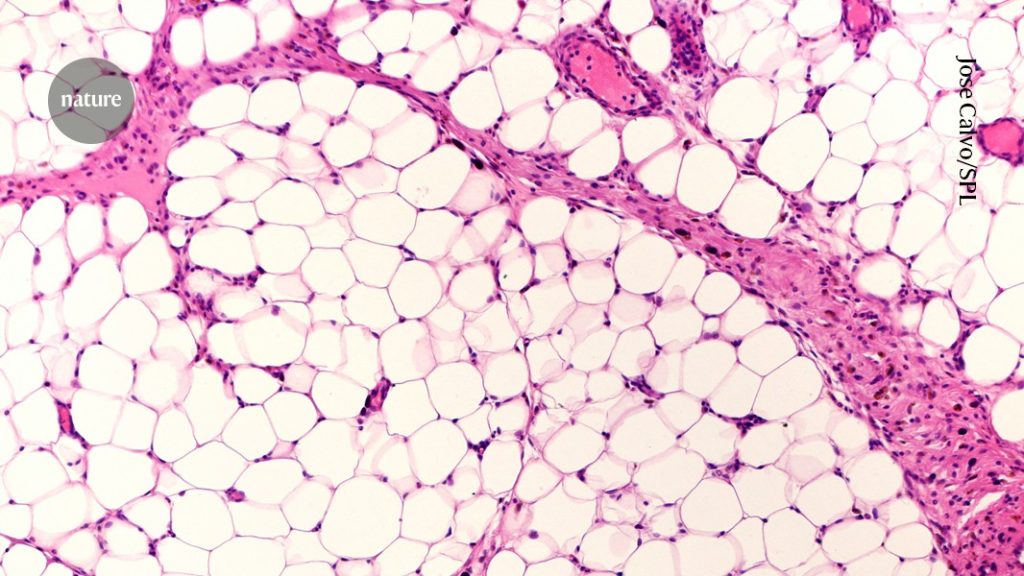

Scientists point out the disadvantages of using a measurement called BMI to measure progress. Body mass index is not perfect. It isn’t an ideal metric for kids because they are growing. “We know that BMI is a poor surrogate for fat mass,” wrote the authors of an editorial4 that accompanied the findings.

Weight related health problems should be considered when defining obese, says Sarah Nutter, a researcher at the University of Victoria in Canada. The authors of the study should have used a more reliable indicator of health than the body mass index.

Source: Should young kids take the new anti-obesity drugs? What the research says

How many pounds are overweight? The role of GLP-1 mimics for treating a child in need of medical attention, and how to warn children

Not much. “We do not have long-term data on the effects [of GLP-1 mimics] on growth and puberty on these young children,” says Ro. There are relatively unknown drugs in the youngest people. No GLP-1 mimics have been approved for treating morbidly obese children in the United States.

The children who took part in the study received a drug for a year and a half, followed by another six months. The study’s authors plan to continue to collect data on the drug’s safety until January 2027.

Ro wants study participants to be monitored to make sure they do not have signs of eating disorders. She says the GLP-1 mimics powerful drugs, and we need to wade carefully.

Children who experience ‘incessant’ bullied by peers know all about it. Ro says that no one seems to talk about the risks. Carrying 250 pounds (113 kilograms) on a 10-year-old body can affect growth and puberty, not to mention the heart, lungs and kidneys, as well as mental health and lifespan, she says. “As in all things,” she adds, “we need to weigh the risks and benefits of treatment versus no treatment.”

The definition of fat as a disease has never been provided by the medical community. It’s typically understood as an excess of body fat, using body mass index, or B.M.I., to gauge who has too much. B.M.I., a tool that divides a person’s weight by the square of their height, is not meant to be used as a tool to determine if a person is healthy or sick. And there’s no consensus on the signs and symptoms that make obesity an illness the way high blood sugar levels are used to diagnose type 2 diabetes, or chest pain and irregular imaging to tell if someone has heart disease.

Diagnosis by B.M.I. was always imprecise; in an era of remarkably effective weight loss drugs, it’s untenable. Consider that 40 percent of American adults are classified as having obesity with a B.M.I. of 30 or above. Over the course of a year, there have been new treatments that cost as much as $1,000 per person per month and supply shortages. It’s about pinpointing who is sick and will benefit from health care and how to triage that treatment and most effectively allocate resources. It’s about ending the murkiness that has surrounded obesity diagnosis for decades.