The elephant in the room? The challenge of preventing Ebola, COVID-19 and monkey pox in the African Union, a technical lead at the WHO

The same tools have been used for control since 1976’s first case of the disease. These measures work best in the sparsely settled countryside, and alone are not viable in dense, complex urban settings.

With effective, available vaccines against devastating diseases, governments could prevent escalation through contact tracing and ring vaccination: in the case of Ebola, perhaps a few dozen contacts of each infected person could be vaccinated. But producing the small number of doses needed to prevent spread is not profitable for drug companies, and donor governments are reluctant to waste money on preventive vaccines that might never get used.

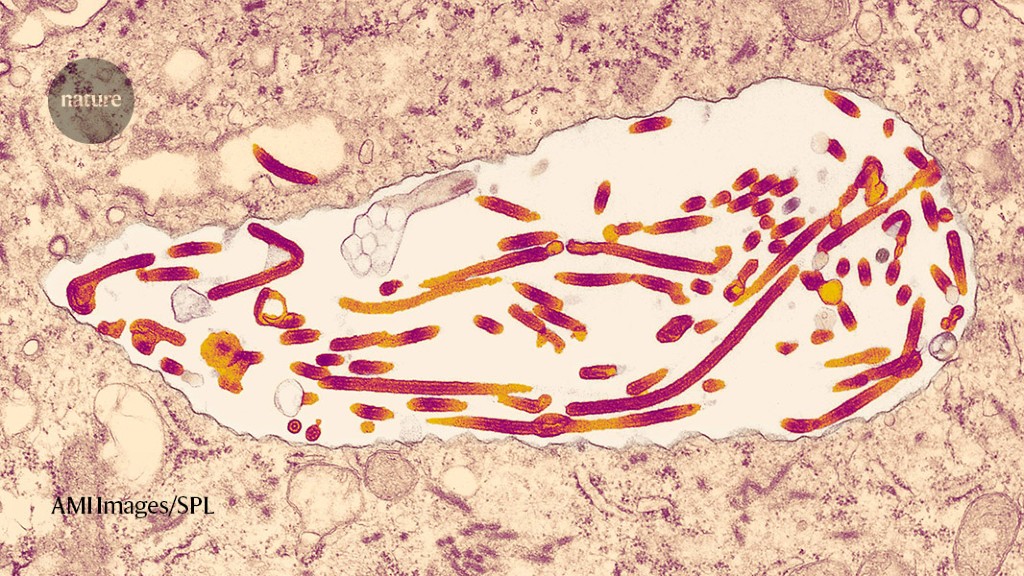

As many people have died as have recovered, it is striking. About 50 percent of people who are ill with the disease die from it. Fruit bats are thought to be the primary host of the virus, but it can spread through the bodily fluids of animals and humans that have been stricken with the disease.

Efforts to provide vaccines and Treatments to African nations have not been moving fast enough, according to a technical lead at the WHO,Rosamund Lewis. Supplies and donations have been scarce; in the meantime, the WHO’s regulatory department is still reviewing data collected from other countries about the vaccines’ safety and efficacy, she says.

Despite that, Tomori doesn’t think that Western philanthropy is the answer. “Don’t buy the story that Africa is poor,” he says. “We are not poor; it is that we are not using what we have.”

Fed up with their countries’ inadequate responses to Ebola, COVID-19 and now monkeypox, a growing movement of African scientists is advocating for improved biosecurity on the continent – that is, protection against pathogens.

The elephant in the room is if it’s possible since African public health systems have been neglected. In 2001, the African Union member states committed to spend 15% of their national budgets on health. Two decades later, that’s happened in only five countries: Ethiopia, Gambia, Malawi, Rwanda and South Africa.

Perhaps the most infamous example was during the West African Ebola epidemic when it took nearly three months to identify the virus in Guinea. WHO reported that the country took so long because “Clinicians had never managed cases. No laboratory had ever diagnosed a patient specimen. The social and economic upheaval that can occur after an outbreak of this disease was not ever witnessed by a government. So when the virus was finally identified as Ebola, it was already “primed to explode.”

Likouala Prefecture is a swampy area in the north of the country, and is one of the least developed regions. He calls Likouala a paradise for pathogens, because there are so many of them. “You know something terrible is going to come out of that area,” he says. It isn’t a matter of time if there isn’t proper pathogen monitoring.

The public health agencies have an important role to play in providing educational programs and coordinating the response according to Tomori. Indeed, the best early warning system might come from those living on the frontlines of novel diseases. “If you take care of that first case, you can prevent an epidemic,” he says.

In the Republic of Congo, Mombouli’s team tried to establish a community-based system for monitoring the health of its citizens. They educated locals about the virus and how it could spread through infected wildlife carcasses, emphasizing the core message: “Do not touch, move or bury the carcass and contact the surveillance network immediately.”

Mombouli thinks that the continent should develop its own epidemic of value chain manufacturing, a term that refers to the entire manufacturing process from acquisition to distribution. Presently, a few African manufacturers have experience making vaccines from start to finish, including the Biovac Institute in South Africa, which produces a hepatitis B vaccine, and the Institut Pasteur de Dakar in Senegal, which produces a yellow fever vaccine.

Last year, WHO chose South African biotech company Afrigen to be the hub for mRNA technology transfer, and 15 spokes have since been identified across various low- and middle-income countries, including six in Africa. Afrigen began training the spokes when they used publicly available information to create their own version of the vaccine that doesn’t require cold storage. The ultimate promise, Mombouli suggests, will be African countries using novel vaccine technology to contain diseases that are spreading on the continent in particular.

“If the company decides to move out,” he says, “then we go back to square one.” Aspen Pharmacare may soon close down its South African plant making COVID-19 vaccines because of insufficient demand due to hesitancy and difficulties giving the vaccine.

Undoubtedly, this will take time, with Afrigen expected to enter clinical trials later this year and vaccine approval coming in 2024, but much can be done in the interim. Beyond fill-and-finish operations, Tomori says that African countries can identify other aspects of the value chain where they can start contributing immediately. One could make glass, rubber, and testing swabs and other items. Each country doesn’t need to produce everything end-to-end, but Tomori says they should all be starting somewhere instead of patiently waiting for international aid.

Things are starting to change. In terms of workers per 1,000, it is one of four African countries that have surpassed the WHO threshold.

This success is due to government prioritization. In a recent paper published in World Health and Population, the authors from the Namibia’sMinistry of Health and Social Services described how they used a WHO tool to diagnose the country’s staffing shortfalls. With this data, they made evidence-based decisions about expanding nurses’ scope of practice and redeploying health-care workers to the regions of most need.

Retention must be a focus of new medical institutions, such as the University of Global Health Equity in Rwanda, and the African General Electric (GE) healthcare skills and training institute.

The dean of the Copperbelt University School of Medicine in Zambia believes that other incentives include housing, land ownership, modern equipment, pathways for professional growth and personal benefits. And if the brain drain still persists, Happi thinks that Western countries should start reimbursing the continent for its educational expenses, given that it costs African countries between $21,000 to $59,000 to train one doctor.

This wouldn’t necessarily stop the exportation of health-care workers, but having the West fork over the money could help African countries replenish their workforce. “People should be honest enough to say that you cannot deplete a continent of its own resources,” Happi says.

That’s not to say African-Western partnerships shouldn’t be pursued. After all, it was Sikhulile Moyo, the laboratory director at the Botswana-Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership and a research associate with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who first identified the omicron variant. Broad Institute and Happi collaborated to deploy COvid-19 tests in hospitals in Nigeria, Africa and the US before any other hospital. A $200 million scholarship fund has been announced by Partners in Health in order to educate future health care leaders in Africa.

Simar Bajaj: The chink in the armour: warning about Ebola in the wake of COVID-19 seven years ago

Simar Bajaj is an American freelance journalist who has previously written for The Atlantic, TIME, Guardian, Washington Post and more. He is studying chemistry and science at Harvard University and is a research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital. Follow him on the social media site, he’s called Simar.

I warned about this problem in a Nature column seven years ago. Despite the COVID-19 wake- up call, this remains one of the biggest chinks in the armour.

The situation isn’t described as short-sighted. Preparing preventive vaccines for a few million dollars per batch should be seen as a small insurance policy to avoid a repeat of the US$12 trillion the world just spent on COVID-19.

It will take seven years to catalyse change so that I don’t write this again. From not talking about the issue to living through a epidemic that daily highlights its relevance, we have come a long way. A change in mindset is in sight, according to me.

Wealthy countries should take the lead. They should ensure that agencies such as the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), based in Oslo, and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI), based in New York City, are fully funded to do this work, which will involve close collaboration with government research agencies as well as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the WHO.

We need a better way. It wasn’t just a matter of locking up and quarks to fight COVID-19. A global effort to develop vaccines and treatments is needed when rich countries are affected by a fatal infectious disease.

Institutional quarantine, meaning separating people who have been exposed to Ebola from their families in an isolation facility for 21 days, or even just quarantining at home, can be hard enough for those who have relatives to care for, or who need those 21 days of income to feed their families. 63 days of lockdown were imposed in two rural districts with a combined population of one million because of the measures we were forced to take in Kampala.

The impact on peoples’s lives was devastating. The societal disruptions that these interventions bring fuel people’s anger and distrust of public-health efforts. There are other ways to curb the spread of the disease.

Mapping would combine three techniques: testing human blood samples for Ebola, testing blood samples from domestic and wild animals and disease modelling. Many countries already have stored HIV surveys for human blood samples, so there is a cheap way to begin. For example, Uganda has the 2004–05 HIV serosurvey. We can use the results of testing to find more locations for new surveys. Funding for reagents and expertise in design and disease modelling are needed by African nations.

A full picture of the longevity of vaccine-induced immunity is unknown for Ebola, but existing evidence is relatively encouraging (Z. A. Bornholdt and S. B. Bradfute Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 699–700. Antibody levels in the blood decrease over six months to one year, but how long T-cell immunity lasts is unknown. An annual vaccine could possibly be plausible, but more data is needed.

There has been a similar delay in African nations accessing tecovirimat, an antiviral approved for smallpox that is thought to work against mpox. More than 6,600 doses of the drug have been administered for compassionate use in the US, as a result of the global outbreak. Africans have access to tecovirimat in clinical trials but they are not available to the rest of the world. Piero Olliaro, a specialist in poverty-related infectious disease at the University of Oxford, UK, has been conducting a small trial of the drug in the Central African Republic, in which 20 people have received it. He says that is much less than a drop in the ocean. “How come we offer tecovirimat to all mpox patients in the US, where the drug is registered only for smallpox, but need a [randomized, controlled trial] to prove it works in Africa?”

Outside of Africa over the past year, the virus has spread mainly among men who have sex with men, through close skin-to-skin contact. Transmission patterns and clinical manifestations of the disease are much harder to pin down in some African countries, where rodent species are thought to naturally harbour the virus and regularly spread it to humans. For example, whereas more than 95% of people infected with the virus in the United States have been men, only about 60% of those who have had confirmed infections in Nigeria are men.

Still, the global focus on the virus has changed a few things in Africa. Because of all the case reports, physicians that had never heard of the disease now know what the telltale signs are, Ogoina says.

Even if a trial can get off the ground, it’s unlikely that enough cases will develop before the current outbreak comes under control for researchers to determine conclusively whether any vaccine is effective or not, Edmunds says. Isn’t it a double-edged sword? It may be bad news for science in that it is good news for public health.

The World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, Switzerland, convened an urgent meeting yesterday to discuss the feasibility of testing Marburg vaccines that are in various stages of development. The chances of a successful trial are very low because of the other control measures that could be put in place to end the outbreak.

At a meeting of the WHO, an epidemiologist from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine said that he needed to emphasize the need for speed.

The Marburg outbreak: Vaccines and vaccines in the Kie-Ntem region of Gabon, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea

The Kié-Ntem province is near the borders of Cameroon and Gabon and is home to the outbreak. It has been involved in 9 deaths among 25 suspected cases, with the first case taking place in early January. This makes it larger than many of the 16 Marburg outbreaks that have previously been detected, Edmunds tells Nature. “Outbreaks have tended to be small and finish relatively quickly after effective interventions have been put in place.”

The exceptions are a 1998–2000 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo that was linked to 154 cases and 128 deaths, and a 2004–05 epidemic in Angola that caused 227 deaths among 252 reported cases.

A vaccine made by Janssen in Belgium uses a human adenoviruses, which is a modified version of a chimpanzee adenoviruses, while the vaccine made by The Sabin Vaccine Institute in Washington DC uses a modified Chimpancho adenoviruses.

Candidates from Public Health Vaccines (PHV) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the International Aids Vaccine Initiative (IAIVI) in New York City and Auro Vaccines in Pearl River, New York, are based on weakened forms of vesicular stomatitis virus — the vector that is used in the first approved Ebola vaccine.

If a vaccine trial in Equatorial Guinea were to go ahead, an independent group of experts that advises the WHO would make decisions about which vaccines to test, says Anna Maria Henao Restrapo, who co-leads the WHO’s R&D Blueprint effort to lay the groundwork for such studies during outbreaks. The permission and involvement of the government in Africa would be required for any trial.