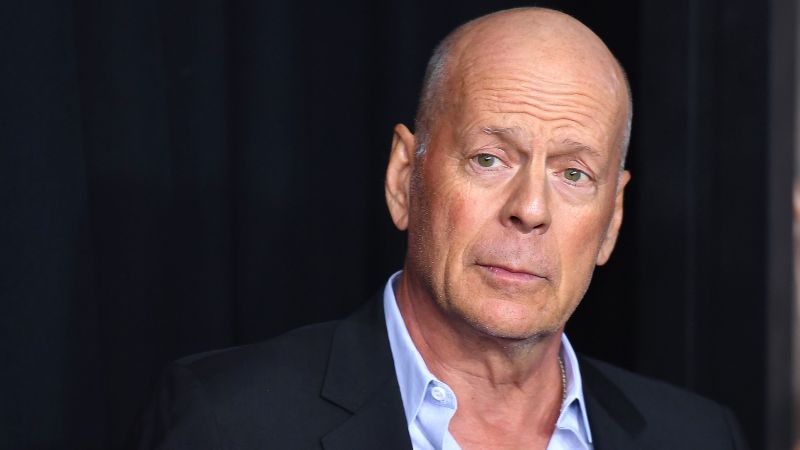

Bruce Willis: A Phenomenological Diagnosis of Aphasia in April 2022 and His New Film “Detective Knight: Independence”

The star’s family stated in a statement that while the news is painful, it is a relief to have a clear diagnosis.

“Today there are no treatments for the disease, a reality that we hope can change in the years ahead. As Bruce’s condition advances, we hope that any media attention can be focused on shining a light on this disease that needs far more awareness and research,” the statement said.

The family first disclosed his aphasia diagnosis in 2022, including the wife and daughters. They stated at the time that he was going to take a break from acting due to his condition and that it would affect his cognitive abilities.

According to the Mayo Clinic, frontotemporal dementia is an “umbrella term for a group of brain disorders that primarily affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. The areas of the brain that are associated with personality, behavior and language are identified by these areas.

Willis’ most recent acting credit is “Detective Knight: Independence,” which was released in January 2023 and is the third installment of the thriller film series “Detective Knight.” Next month he will be releasing an action movie, “Assassin”.

When Alzheimers Walk: Bruce Willis, 67, Is Aphasia Diagnosed with Frontotemporal Dementia

“Bruce has always found joy in life – and has helped everyone he knows to do the same. The statement added that it had meant the world to see that sense of care in him and all of us. “We have been so moved by the love you have all shared for our dear husband, father, and friend during this difficult time. We can help Bruce live as full a life as possible with your continued compassion, understanding, and respect.

After retiring from acting in March 2022 due to a speaking disorder called aphasia, Bruce Willis, 67, has since been diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia, his family announced Thursday.

An FTD diagnosis is akin to a death sentence. There is no preventing it. There is no stopping it. There is no slowing it down. People with FTD typically die within six to eight years of its onset, usually from vulnerability to infections or accidents. To be given this diagnosis is to open a door into a hellish world where medical science, as well as the health and caregiving systems, seem to collectively shrug their shoulders, shake their heads and in so many words say to patients and their loved ones, “There’s nothing we can do for you.”

“Aphasia really means problems with language, and that can vary from having trouble finding your words to understanding what people say. It can happen due to a brain abnormality, like a stroke, or progressive neurodegenerative condition.

Another type affects motor neurons, and can show up via an inability to swallow, rigid muscles, and difficulty in using hands or arms to “perform a movement despite normal strength, such as difficulty closing buttons or operating small appliances,” according to the National Institute on Aging.

In the beginning, it can be difficult to know exactly which type of FTD a person has — or even whether it is FTD — because symptoms and the order in which they appear can vary from one person to another and depend on which parts of the frontal or temporal lobes are affected.

In behavioral FTD, people rarely have issues with memory. The National Institute on Aging says that they struggle to sequence their thinking because of problems with setting priorities. They may parrot the same activity or word again and again, become disinterested in life, and act impulsively — saying inappropriate words or doing things others might perceive as embarrassing.

In primary progressive aphasia, or PPA, the person might have trouble speaking or understanding words or might slur their speech. They may not recognize familiar faces over time. Some may become mute.

PPA can begin with difficulty finding words, so people will use simpler words or generic words for things they can’t remember.

It goes with the territory of aging, but when the language is not as effortful as it could be, or comprehension is getting worse, that is a sign that someone should see a doctor.

Motor neuron FTD disorders may not affect memory, cognition, language or behavior, especially at first. The inability to control movements or issues with balance and walking may be the initial signs. A hallmark sign of one of those disorders, progressive supranuclear palsy, is difficulty with looking down or other eye movements.

If certain parts of the brain are Shrinking or Showingsigns of Alopecia, a brain magnetic resonance photograph can tell us about it. He said that they’ll do some blood tests to make sure there aren’t some other causes of cognitive impairment like thyroid disease or vitamin B12 deficiency.

We will also do brain metabolism image at times. “It’s Positron Emission Tomography or PET imaging, and that can tell us which parts of the frontal lobes or the temporal lobes are involved.”

Speech-Language Pathologist for Patients with Progressive Dementing Syndrome: The Role of Physical and Occupational Therapy in Alzheimer’s Disease

It is vital that people with a progressive dementing syndrome such as FTD are able to continue eating well, exercise and stay connected with their friends. Those activities are not medications, they’re not curing the disease, but they can help your brain work as well as possible,” Paulson said.

A speech-language pathologist can help determine the best strategies and tools for an FTD patient struggling with language skills. Neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s, may benefit from physical or occupational therapy.

“I’ve seen patients who completely lose their speech and yet they go out and take their camera and take beautiful photographs of the lives they’re living. They can’t tell me in words, but they can tell me in pictures,” Paulson said.

I tell all my patients not to let the disease affect them. He said you own it. “Sure, you’ve lost some skills because of the illness you have, but you still have lots of skills left and you work with the skills you have.”

Diagnosis of FTD tends to happen between a person in their 40s and 60s, while Alzheimer’s happens at a later age. Alzheimer’s is tied to issues with spatial orientation, like getting lost.

Brain scans, called brain scanning, are used to diagnose FTD. The patient’s medical history is correlated with the results. About 30% of people with frontotemporal degeneration inherit the disease; there are no known risk factors.

What Happens When a Poor Dad Gets Closer to Home: The Implications of FTD on My Father, My Sister, and My Family

The director of communications at ideas42 is the one mentioned in the next paragraph. She is also one of the founders of Behavioral Scientist magazine. The views are of the writer. CNN has opinion on it.

Many people are learning about a disease for the first time after reading about it from the family of one of the victims. But few people can comprehend its disastrous and destructive effects. The media states it is a “heartbreaking disease.” “Devastating, prevalent and little understood … the cruelest disease you have never heard of.”

But my family has heard of it. We’ve spent the last five years living with it as we lost my father bit by bit, adapting to its many indignities, powerless as he lost first his impulse control, then his empathy, then his speech, then his mobility and, finally, the ability to swallow and the strength to keep his heart pumping. I know what’s coming for Willis – and his family. It’s something I would never wish on my worst enemy.

My sister and I cared for my father at home. In some ways we were lucky. In the midst of some of the more shocking periods of decline that came with FTD, he was still able to contribute, like a lack of immunity, paranoia and a lack of consciousness if someone were very sick. He never said an unkind word to my sister or me, never became dangerously agitated or threatening.

When my father decided that he needed his two daughters to take over his bathing and hygiene, he told us through his timid posture that he was embarrassed and ashamed, even though he knew his daughters would do a great job. He allowed us to care for him as much as we could, with gentle pleading.

Because Iranians value family above all, my father had been in frequent, almost daily, contact with my sister and me throughout our adult lives. So we noticed his personality changes early enough that he never gambled away his life savings, lost his home, fell prey to a predatory scam, got into a dangerous accident, got fired from a job or put the lives of his family in danger – all things that can happen to people with FTD early on as the parts of the brain responsible for judgment atrophy.

According to the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, there at least six known clinical trials that are active for disease-modifying drugs. There is one longitudinal study actively recruiting patients and families, the ALLFTD Study, conducted by a consortium of researchers and funded by the National Institutes of Health, including input from patient and caregiver advocates like the Remember Me podcast. But it’s currently only funded through 2025.

Source: https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/25/opinions/bruce-willis-frontotemporal-dementia-experience-salasel/index.html

Is it Too Late for My Dear Dad? Hopefully the New Year will be Alive and Well for Other Patients with Frontotemporal Dementia

It’s too late for my beloved father. On Friday, just as Iranians around the world were celebrating Nowruz (new year), my own loved ones gathered for Chehelom, the heart-wrenching traditional 40th day observance of mourning.

But maybe there’s enough time for others. 50% of the time FTD is passed on to a child. It might not be too late for my sister, for my children and for some potential sufferers of frontotemporal dementia if a breakthrough in treatment is reached in the coming years.