“What are the hardest things to do in academia?” says Petra Hemnkov, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Africa

Two people were in their twenties when they met in Montpellier, France. While Altinli was finishing his PhD on how infections develop, Chevalier had just finished his thesis on southern Africa. Both were excited for a career in academic research. After my PhD, I was expecting to be a research fellow for at least five to six years. “I felt a sense of satisfaction about that prospect” says Chevalier.

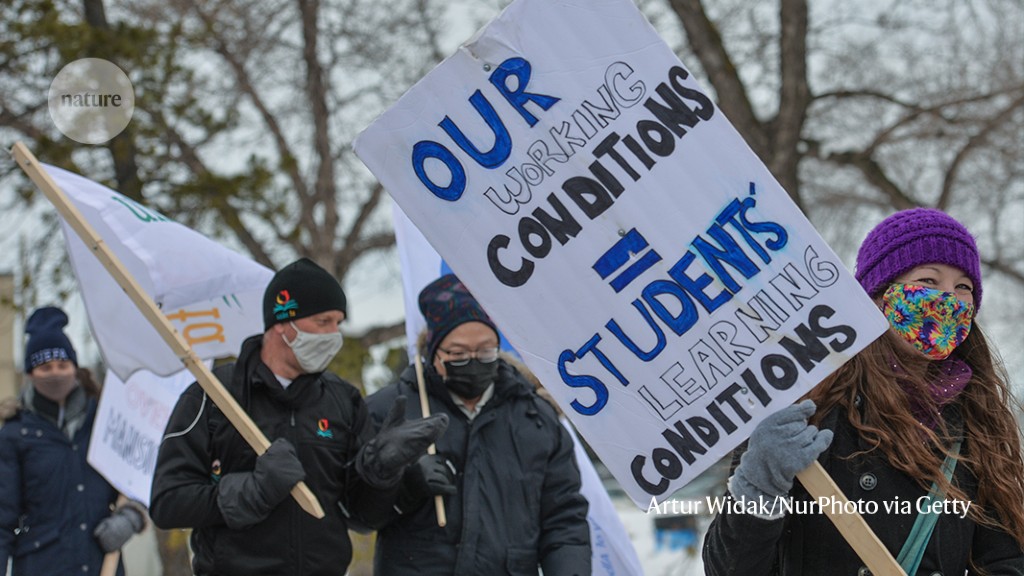

The strike action taken by some postdocs in some parts of the world is an indication of how bad things have become. Some institutions are responding, partly as a result. Improving the experience of being a Postdoc is the right thing for others to do.

“People have been talking about this for nearly my entire life,” says a respondent to Nature’s latest survey of postdoctoral researchers. These words highlight how, compared with people who have similar qualifications but work in other sectors, low salaries and insecure working conditions are part and parcel of the postdoc experience.

Petra Hemnkov sees herself in nature’s data. She has been to Australia and Australia and then to Hungary, then to the Czech Republic, then to Spain, and finally to the United Kingdom. This August, she started a three-year assistant professor position at Aarhus. The chances of progressing to a permanent job are very small even if she says it looks fancy. She will be 40 when the appointment is over.

There is an emotional cost to existing in a state of impermanence, Heřmánková says — simple things, such as not being able to accumulate belongings, start to weigh heavily after a while. I only took one suitcase and one backpack when I left Australia. I haven’t had a TV since 2015,” she says. She has not been able to buy a house, and with rising property prices both in Denmark and in the Czech Republic outpacing salaries, she is uncertain if she ever will. However, she and her Czech husband did have a baby earlier this year. Hemnkov was waiting for more permanency before starting a family. When she realized they were not materializing, “we decided to just go for it”.

A Nature survey shows that half the postdocs surveyed in Africa earn less than US$15k a year, and Van Goethem secured his current position at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia. The pay is significantly more than he would earn back home, and his employer subsidizes his living expenses and transport costs, meaning he can comfortably support his wife and child who remain in South Africa. “I guess I’m kind of hacking the system for now,” he says. But the future is uncertain. Moving back to South Africa — even to a permanent academic position — would mean a drastic pay cut. Being away from his family makes him sad. “Doing science is still so rewarding. But the personal costs are many. He says it is like eating food off a paper plate.

Nature postdoc survey respondents in their thirties describe the uphill struggle to start a family. Comments have been lightly edited for length and clarity, and, when necessary, translated into English.

“It’s hard to combine a postdoc with having a family. I was told off for missing meetings held outside of childcare hours and I think that I only got my current postdoc because I didn’t tell my employer about two of my three children.” — Female health-care researcher, Germany

“The pay is abysmal and the only way that I can afford my kid is because my spouse has a job that actually pays what she’s worth.” — Male physicist, United States

“I technically had parental leave, but the regular renewal of my short-term contracts made me ineligible to use it for any of the three children I adopted.” The United States has a female ecologist.

“The salary is very low and we don’t receive benefits such as childcare or paid vacation leave. Even as a postdoc, there is no independence. I can’t decide on the budget or project even if I get a grant. — Female biomedical scientist, Mauritius

Being in science is like a lottery. Effort won’t ever translate into success. People will get ahead. — Male marine microbiologist and bioinformatician, Colombia

How lucky are women to be able to afford child care? A study in the U.S. Postdocs in their teens tire of putting life on hold

I can’t afford child care, and I’m considering leaving the workforce to do so. As a woman of colour, I feel even more marginalized and isolated.” Female health-care researcher in the United States.

Two weeks of maternity leave is all my current university has to offer. And my state banned abortion within weeks of the US Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade. I was surprised by the resulting anxiety and how this affected my mental health.” The physicist is from the United States.

Nature says the availability of paid parental leave and subsidized daycare is still patchy. Those who say their salary or benefits package includes subsidized childcare are still firmly in the minority, although the proportion has increased from 14% in 2020 to 17% this year. Less than a third of male respondents said they were not able to access paid parental leave this year, compared to less than one third in 2020, but the proportion has increased over the last couple of years.

Source: Falling behind: postdocs in their thirties tire of putting life on hold

Postdocs: Embracing the 21st Century? Commentary on the Post-doc Workforce in Canada and the United States

Chevalier says he was warned during his PhD that the academic job market would be tough. After a couple of years as a researcher, Altinli is getting ready to move to another country and look for a permanent job. She isn’t ruling out an industry post but prefers academia. They have agreed that where they settle will be determined by which of them gets a permanent job first.

The second global survey of the post-doc work force, exploring over the past three weeks, has shown signs that highlighting problems is leading to action.

There are overlapping reasons for this change. In the past few years, funders and employers around the world have started to pay attention to the plight of postdocs. Postdocs have become financially strapped due to rising living costs. In Canada and the United States, early-career researchers are getting organized and are taking industrial action to demand higher salaries.

In the wake of MeToo, Black Lives Matter and other global antidiscrimination movements, many universities have introduced policies to boost diversity and promote inclusion. The need to support academic employees well-being has been thrust onto the spotlight thanks to the COvid-19 Pandemic. More than half of postdocs told Nature’s survey that they have considered leaving their scientific field because of mental-health concerns. Some organizations, including the Francis Crick Institute in London, have introduced mental-health first-aid schemes to support staff members.

The mismatch between ambition and reality shouldn’t be a problem for universities to treat postdocs better. Nor should the fact that most researchers do not stay with the same institution for decades, as might once have been the case. Postdocs should still be valued as employees, and employers held accountable for their treatment.