Cell-derived blastocysts can help understand the early stages of embryo development in macaques without the ethical dilemmas of real embryos

The early days of an embryo are shrouded in mystery because it pulls a disappearing act. Once a sperm finds an egg, it begins a roughly weeklong journey to the uterus, becoming a tiny ball of cells along the way. When it reaches its destination, it attaches to the wall of the uterus, disappearing from view.

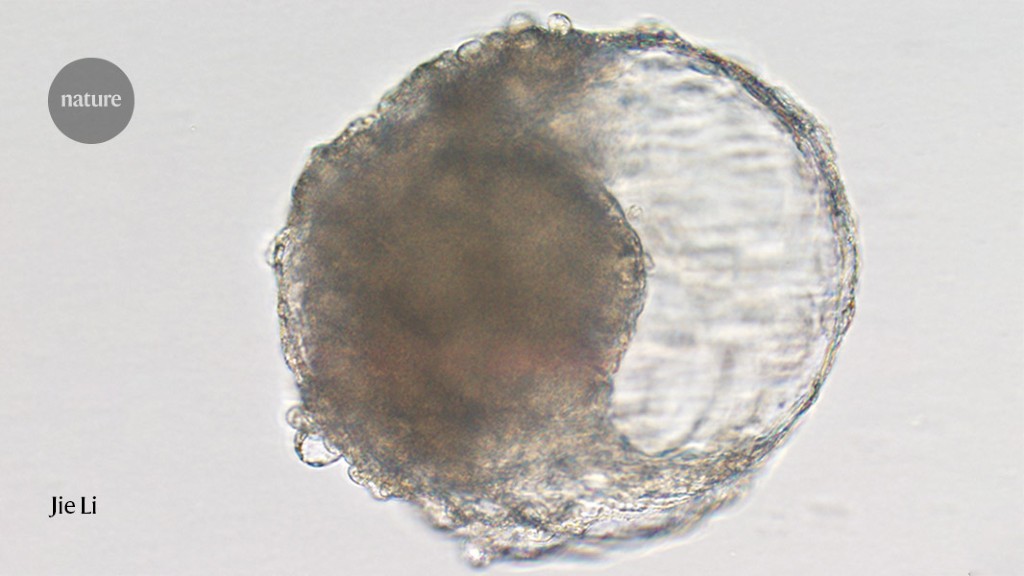

Scientists have created balls of cells that resemble embryos and trigger signs of early pregnancy in macaques. The stem-cell-derived blastoids could help researchers understand human embryo development without the ethical dilemmas of using real embryonic cells, according to a study published today in Cell Stem Cell1.

Nicolas Rivron says that the structures are not the same as natural embryos because they did not develop normally. “It’s easy to form a structure that looks like a blastocyst,” he says. The looks can be deceiving.

“They look very convincing,” says Kotaro Sasaki, an assistant professor of biomedical sciences at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, who studies primate embryology and human development and wasn’t involved in the study. “It looks like they have all the cell types that are present normally in embryos.”

When profiling approximately 6,000 individual cells, they found genetic differences like those seen in natural blastocysts. Some cells expressed genes associated with the endoderm — the innermost layer that eventually forms the linings of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts — whereas others were enriched with genes involved in placental development. But the blastoids weren’t a perfect reflection of natural blastocysts — some cells could not be classified, and some didn’t express as much protein as expected.

Not having the right cells, structure and gene expression in embryolike structures is an indication of more to embryo development than just being an embryo.

Furthermore, embryo models that fall apart in the womb could offer insights about the factors that lead to miscarriages and implantation failure after in vitro fertilization treatments, says Alexandra Harvey, a developmental biologist at the University of Melbourne in Australia. “If these models are actually failing at that stage, we’ve got to work out what other markers we need to be looking for at earlier stages,” she says.