The world needs a new indicator of economic progress: warnings from the United Nations, Brazil, South Korea, and India in the 21st century

The numbers are heading in the wrong direction. The United Nations set to end poverty and inequality and protect the environment will be missed if the world goes on with its current track.

The trends were there before 2020, but then problems increased with the COVID-19 pandemic, war in Ukraine and the worsening effects of climate change. Pedro Conceio, lead author of the United Nations Human Development Report says that the world is in a new uncertainty complex.

One measure of this is the drastic change in the Human Development Index (HDI), which combines educational outcomes, income and life expectancy into a single composite indicator. After 2019, the index has fallen for two successive years for the first time since its creation in 1990. I think this is not a one-off or a blip. Conceio says that he believes this could be a new reality.

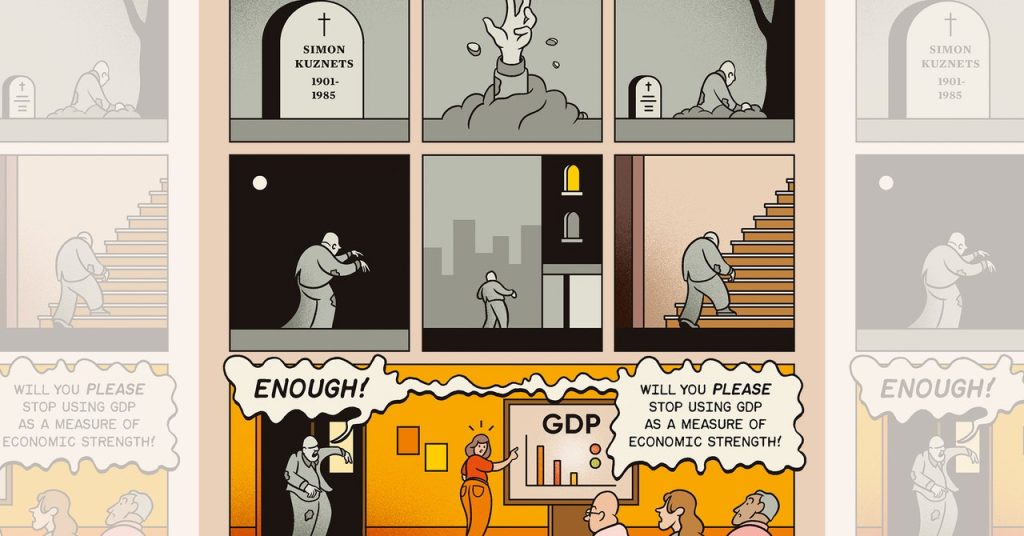

Guterres’s is the latest in a crescendo of voices calling for GDP to be dropped as the world’s primary go-to indicator, and for a dashboard of metrics instead. In 2008, then French president Nicolas Sarkozy endorsed such a call from a team of economists, including Nobel laureates Amartya Sen and Joseph Stiglitz.

Amid the perfect storm of food and energy crises, in 2023 politicians worldwide will finally start adopting alternative economic indicators. China has in the past promoted the so-called ecological civilization, setting explicit targets for nature and resource use. In July 2022, its Politburo surprised the world when it did not mention the growth target in a statement after its quarterly economic meeting. China Daily floated the idea that there’s a need for a new “development” yardstick and other indicators, like employment and price stability.

The world’s main index of economic progress is GDP, which is a measure of economic activity. By a commonly used definition, this means the sum of consumer and government spending and their business investments, added together, giving the value of exports minus imports. When governments and businesses talk, as they regularly do, about boosting ‘economic growth’, what they mean is boosting GDP.

GDP can also be important to politicians. When India leapfrogged the United Kingdom to become the world’s fifth largest economy earlier this year, it made headline news. According to reports, China had delayed publication of its latest quarterly GDP figures so they would not be seen during the Communist party’s national congress, which bestowed a third term on the president.

More recently, environment ministers have found that GDP-boosting priorities have got in the way of their SDG efforts. The environment minister of Costa Rica, Carlos Rodrguez, asked his finance and economics coworkers to consider the impact of economic development on water, soils, forests and fish. Rodrguez said that they were concerned about possible reductions in GDP calculations. Costa Rica didn’t want to be the first country to implement such a change only to possibly see itself slide down the growth rankings as a result.

It has been the same in Italy. In 2019, then research minister Lorenzo Fioramonti helped to establish an agency, Well-being Italy, attached to the prime minister’s office. It was intended to test economic policy decisions against sustainability targets. “It was an uphill battle because the various economic ministries did not see this as a priority,” says Fioramonti, now an economist at the University of Surrey in Guildford, UK.

The next revision to the rules is under way and is due to be completed in 2025. The final decision will be made by the UN Statistical Commission, a group of chief statisticians from different nations, together with the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the network of the world’s wealthy countries.

Because the UN oversees this process, Guterres has some influence over the questions that the review is asking. As part of their research, national statisticians are exploring how to measure well-being and sustainability, along with improving the way the digital economy is valued. Economists Diane Coyle and Annabel Manley, both at the University of Cambridge, say that technology and data companies, which make up seven out of the global top ten firms by stock-market capitalization, are probably undervalued in national accounts5.

According to Peter van de Ven, the lead editor of the GDP revision effort, some aspects of digital-economy valuation, as well as putting a value on the environment, won’t make it into a revised GDP formula. One of the reasons, he says, is that national statisticians have not agreed on a valuation methodology for the environment. Nor is there agreement on how to value digital services such as when people use search engines or social-media accounts that (like the environment) are not bought and sold for money.

Yet other economists, including Fenichel, say that there are well-established methods that economists use to value both digital and environmental goods and services. One option is to ask people what they are willing to pay for the privilege of using an internet search engine or a forest. Another method is to ask what people would be willing to accept in exchange for something else. In the experiment, the scientists computed the value of social media by paying people to give up using it.

Economist Gretchen Daily at Stanford University in California says it’s not true that valuing the environment would make economies look smaller. It all depends on what you value. Daily is among the principal investigators of a project called Gross Ecosystem Product (GEP) that has been trialled across China and is now set to be replicated in other countries. GEP adds together the value of different kinds of ecosystem goods and services, such as agricultural products, water, carbon sequestration and recreational sites. The researchers found that the total GEP in the Chinese province of Qinghai was larger than the GDP.

In 2023, as the world faces unprecedented climate breakdown and economic recession, the scramble for alternatives to GDP will begin in earnest. Navigating fractious politics from this shift will be tricky, as critics will see them as attempts to shed responsibilities. But ultimately the purpose of new economic indicators will be about delivering better results for people, and there will be much anger if policymakers fall short.

The annual trends briefing is contained in the story. Download the magazine or read more stories from the series here.

The Better Life Index: An indicator of economic well-being for the New Zealand government and for its economic policies and measures of human rights in the era of globalization

China is not the only one. In a paper published last year, the German Economic Ministry contemplated new indicators of welfare, which included equality across local regions, as well as sustainable employment and participation. New Zealand’s Living Standards Framework, developed by the Treasury, includes a dashboard which measures a range of well-being indicators and is embedded as the organizing principle of its national budget.

The Better Life Index takes into account air pollution, work life balance, and housing affordability.